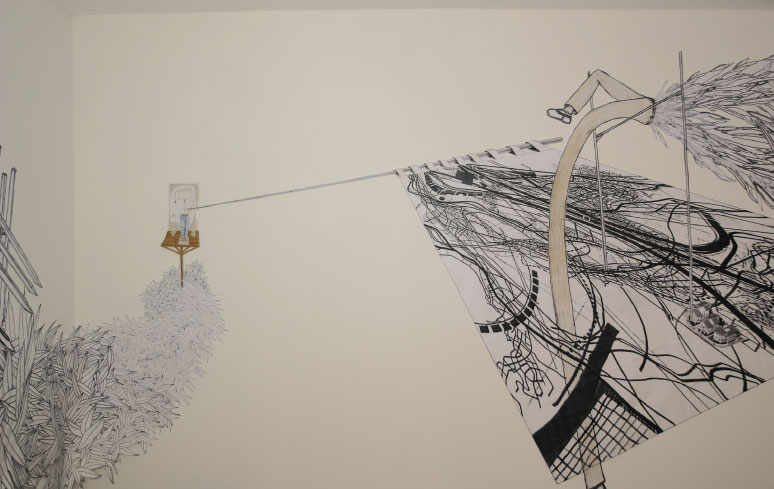

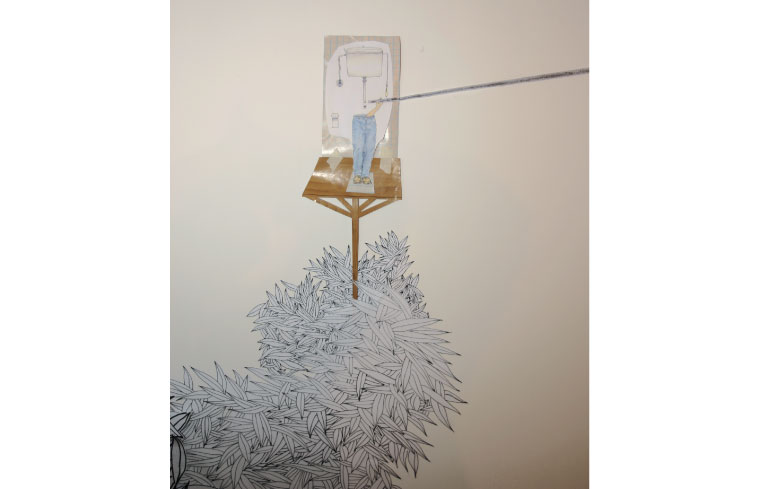

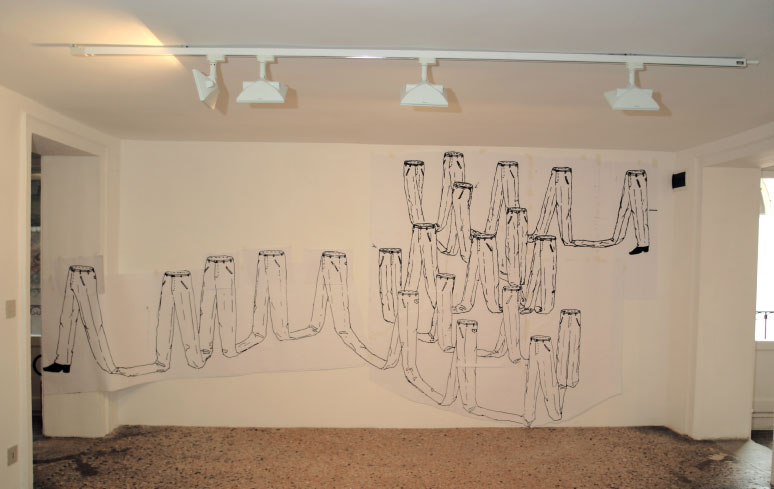

I promise, You Will Love Me Forever, 2005

Drawing Installation

Pencil, marker, photocopies on paper, collage on wall

Dimensions variable

One can only think when one is not alone By Chus Martínez

If you were to ask me about the opening sentence of the books that have most impressed me, Don Quixote is perhaps the only one that I would be able to remember. And in spite of what you might imagine, this memory has nothing to do with reading the book and then wondering about the whys and wherefores that made the author decide to begin his narrative in this particular way rather than any other. In the case of Don Quixote, and given the cultural background I come from, first came memorisation and then reading. As children, everyone in Spain makes an effort to learn off by heart the first sentence of a book that most of us know by reputation only and which is, we have been taught, not just a key work in so-called “universal literature”, a concept that is becoming increasingly clear yet less clarificatory, but also a means to understand the “Spanish” character, another complex concept.

Don Quixote begins, like lots of films made in America for TV, by situating the viewer, or in the case of Cervantes, the reader, in undistinguished kind of place, a run-of-the-mill home in the sitcoms that we might all identify with. This “village of La Mancha, the name of which I have no desire to call to mind” is the starting point of a series of adventures that occur in this location that has no name because it belongs to all of us, a place we identify with a particular locality as we see fit. This is a brilliant strategy for freeing oneself

from etymologies, though Cervantes did not count on the unbearable lightness that ambiguity gives rise to in all the forms and echoes of the modern state, with the result that on the four-hundredth anniversary of the publication of this illustrious work of literature, a handful of eminent scholars and philologists can pronounce, after years of serious inquiry, upon the precise location where Don Quixote begins.

Remembering the opening sentence is not synonymous with remembering the entire book. Nevertheless, it is fascinating to analyse why certain ways of situating ourselves in reading should be recorded in our memory whereas others are not. Kundera, an author read, loved and reviled by all, is a case in point. In one of his books, Immortality, he looks out of the window of his home and watches a woman in late middle age who is not particularly attractive, in his eyes at least, go through an exercise routine in a swimming pool, following the instructions given her by a much younger lifeguard at the edge of the pool. The woman hangs on to the rough concrete poolside, trying to do the exercises. The author’s persona is momentarily distracted and then turns his attention back to the scene, by which time the woman is now out of the water and making her way towards the changing rooms. Just before she gets there, she lifts her hand and waves to say goodbye. This gesture of farewell to her instructor, so Kundera says, has an incredible effect. The woman waves as if unaware of her physique, heedless of the fact that she is wearing a swimming costume and that her face and body no longer have any charm. She waves like a younger woman full of vim and vigour, and for a second physical reality is transfigured into another image, one that is in the mind’s eye yet truly experienced, an image that reveals the true personality of this woman and, when all is said and done, her beauty.

Beginning a narrative by drawing attention to a gesture, in other words a trivial deed that is capable of changing things, is especially important in the context of the presentation of a national pavilion in which two artists, Konstantia Sofokleous and Panayiotis Michael, represent the island of Cyprus. “Gravy Planet”, the umbrella title for the project, is a context created artificially with a view to revealing the important aspects concealed behind the mass of chance events, circumstances and work that lead up to a landing on this strange planet. The pavilion could itself easily be read as a ‘gesture’ that is in part trivial and in part capable firstly of presenting the work of these two artists in an appropriate manner, and secondly of evincing the possibilities of a community that we do not see but which they are a part of, in other words, the artists and cultural agents of their country. Like the village at the beginning of Don Quixote, Gravy Planet is nowhere; it is a world created for the specific occasion of the Venice Biennale. Both the artists have, from their own individual standpoint, chosen drawing as a medium to allude to questions to do with the socio-political situation they work in, but using a language that does not attempt in any way to illustrate it.

The title, taken from an old sci-fi classic, alludes to a dystopian reality, a planet somewhat in decline by the standards of the cosmos in which we find, not the triumph of progress or the republic of virtue, but a looser reality in which personal resources and the ability to grasp the opportunities that come our way have eclipsed the ideals of the common good. But aside from making reference to the decadence of the modern project, this particular planet demonstrates, through the choice of the genre of sci-fi, the potential ability of the margins to alter the map that always places the ‘metropolis’ in the same place. It is in the spaces in which the norms are dictated by the paradoxical rather than a previously agreed set of values that the disciplined limits of the modern state can fracture, generating a new vocabulary that breaks with the logic of events.

The works of these two artists could, therefore, easily adopt the formula of a critique of the present on the grounds that it is not what it could or ought to be, something that is characteristic of the disillusionment of the echoes of the European left-wing in our cultural life. For this reason, a possible ‘political’ reading of this kind of work is difficult for a spectator educated in the circumstances that I have just outlined. Even so, the artists’ choice of drawing as their medium and the themes they both opt for point to an urge to situate the need to revise cultural references at the heart of the debate. Such references might include a traditional rhyme that is part of the oral literature intended for children—the starting point for one of the animated pieces by Konstantia Sofokleous—or the distortions that a full and omnipresent awareness of belonging to a society marked by conflict, but also by an etymological reading of history, can cause in our understanding of what the notion of the ‘modern subject’ might mean, as in the case of the mural collages by Panayiotis Michael. When a community falls apart due to dissent, cultural agents and artists are capable of furnishing precise accounts and analysis of a world predisposed towards apprehension and to thinking that the cause of all the ills that beset us in our highly developed societies is uncertainty.

The works of these two artists spring from an intense search to find what one could describe as an etiological myth. In other words, in the face firstly of readings of the present that constantly exploit absolutist notions of identity and which build our everyday lives on the basis of suspicion, and secondly of the veiled recourse to myth as an explanation, the works of these artists use the fragile and ephemeral as a valid means to neutralise the inexorable and to prevent the ‘condensation of meaning’. This, then, is their strategy designed to increase the number of readings, but also to highlight the importance of generating our own readings of the present. An etiological myth is nothing but a fable that does not aspire in any way to historical truth. Such myths are narratives intended not to give an account of any origins but instead strive to endow the here and now with meaning. The importance of revisiting Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll is not due to the legitimacy of the text in its own day as one of the key works of Western literature, but because its translation into other languages in other contexts frees us from the security offered by culture writ large.

The overall title of Michael’s piece I promise You Will Love Me Forever is another example of the selfsame thing. The title poetically expresses the greatest source of anxiety in our times: the desire for certainty. Though security and certainty may seem to be one and the same thing, they are not synonymous. Security signifies that everything that we have achieved or won will remain ours and will retain its value as a source of pride for the individual or the collective. Security allows the world to be perceived as a place governed and ordered by an established number of rules that are in turn founded on a solid base of values held by the community. In other words, security implies an agreed form of rectitude, which obliges the individual to abide by the rules, regardless of his or her personal desires. Certainty is a somewhat different concept. If we are to be certain of something, we must first learn the difference between what is reasonable and what is foolish, between options that are viable and those that are beyond the bounds of possibility. One of the features of contemporary societies is the multiplicity of roles we play in our everyday lives. We are exposed to countless moments when we must make a decision, devise a strategy, maximise our resources and determine whether the step we are about to take will turn out to be a good or a bad idea.

I promise, You Will Love Me Forever is in itself the utterance of a promise in a society in which there is no system of values to force the speaker to keep it. Far from the security offered by ‘traditional’ societies, in which personal happiness can and must be sacrificed for the good of a value such as fidelity, the title of this work immediately presents the spectator with the unavoidable doubt that this is in fact possible. We do not question intentions, but we know that such intentions are inevitably in conflict with a desire to see personal or collective freedom as a constantly expanding process, in which decisions are made with a view to increasing the range of possible options and ways of life, and in order to avoid being restricted to a single way of determining our personality, so that we can instead live in a flow of possibilities that allows us to change if a judicious reading of circumstances demands it. We have no guarantee whatsoever that

people will keep their promises, but we can devise a set of criteria that make it possible to determine whether it is necessary for them to be kept. Nothing is sure in advance.

In the case of both Konstantia Sofokleous and Panayiotis Michael, it is important to consider to what extent their choice of medium allows them to play with notions such as those discussed above: ambiguity, the value of the ephemeral in contrast with the robustness of the habitual, the need to develop permeable narratives subject to change and decision-making, narratives that are fragile yet at the same time capable of protecting us from single readings or formalistic hierarchies that give precedence to certain mediums and languages over others on the grounds that they represent shared values that the entire community should be proud of. Drawing in this context does not represent pride but the capabilities of a certain sector of the cultural and artistic community, regardless of the medium chosen for their work.

In the context of the pavilion, drawing provides an unusual capacity to superimpose the changes and different speeds of working that lead to the final result. This result should not be seen as a resolution but as a particular chapter in each of the projects. Drawing is far from being simply a precursor but is instead, one might say, the most appropriate language for expressing the need to open up a vast field of imaginative and cultural action. The low resolution of drawing provides the perfect cover for setting out on an adventure that goes beyond art. The artists’ ambition is to use the age-old urge to begin tracing lines on a piece of blank paper, a distinctive feature of an approach aimed at studying the relationship between the sphere of the personal and its relationship with collective ambitions. In contrast with the famous assertion of the idealist philosopher George Berkeley “to be is to perceive or to be perceived”, the type of experience offered by Sofokleous and Michael’s works raises the issue that there is indeed a reality over the horizon of the verifiable and that it is precisely this territory that can furnish us with the tools we need if we are to confront reality with renewed energy and consider not one plausible future but thousands.

How to become modern and return to sources By Sarah Lowndes

Roland Barthes once wrote that ‘In the multiplicity of writing, everything is to be disentangled, nothing deciphered; the structure can be followed, ‘run’ (like the thread of a stocking) at every point and at every level, but there is nothing beneath’.1 The specificity of the image of the laddered stocking seems to shoot out of the prose as a point of contradiction – eliciting thoughts of ways to stop a ladder: a touch of nail varnish, or in a pinch, a smudge of soap. Letting a ladder carry on running would surely be a sign of being quite far gone. In this one troubling phrase Barthes reveals the passivity that attends post-structuralist thought - and the way in which much postmodern theory endorses the logic of modern capitalism while unmasking its ideals.2 As a counterpoint to Barthes’s idea of there being ‘nothing beneath’ we could read the visual text of the Dorothea Lange photograph A Sign of the Times – Depression – Mended Stockings – Stenographer, San Francisco, c.1934. The image is framed to reveal only the hem of the stenographer’s black skirt

and coat (still good) and then damning, a painstaking line of tiny stitches descending down each of her shins. This photograph reminded me of the way my father’s mother still maintains the wartime practice of darning her stockings, although of course the years of rationing have long since passed. In looking at Lange’s photograph and thinking about my grandmother, it seems obvious that the real that Barthes claims cannot be deciphered persists in arresting details such as these. It also seems obvious that to adopt a position as a spectator, as one who watches the ladder run, is to become complicit in the machinations of the existing system. For the politically committed individual the question then arises of how best to proceed. It is this question that forms the basis of the work of the Cypriot artist Panayiotis Michael.

Panayiotis Michael was born in Nicosia in 1966, eight years before the Turkish and Greek communities on the island were forcibly separated following the Turkish invasion. Michael has commented that, ‘The period of transition of a change from one situation to another, from one stage to the next – whether these act upon an individual or a socio-political level – is the fundamental issue that attracts me the most.’3 In his work, we see Cyprus constantly emerging in a variety of forms: as a romantic Other, as a site of dispute and perhaps most importantly, as a recognisable and specific place. The history of Cyprus has been largely dictated by its position at the ‘maritime crossroads’ of the eastern Mediterranean basin, which has meant that the island has been fought over and settled by numerous invaders. In recent years, Cyprus, like Lebanon, has become not only the scene of a local dispute but also the source of an actual and potential international confrontation.4 The 1974 Turkish invasion - following a coup by militant Greek Cypriots instigated and organised by the Greek junta - resulted in a green line bisecting the country, which remains in place today.5

The metaphor of the green line (the front, the zone, the border) operates in Panayiotis Michael’s work as a means of examining personal and political divisions. Michael directly addressed the issue of borders in the performative piece Ode to Joy (1999-2000) – in which he sewed together the borders of European countries using green thread. For six hours he sewed, tearing areas of the map and bunching others together, creating a useless and unreadable relief map. This performative action posited the individual voice against the ‘official knowledge’ reflected and sustained by the map. This altered cartography was an attempt to demonstrate the potential risks both of accession to the European Union and of the wider corporate globalisation project. In sewing together the borders of each country, Michael deliberately effaces the differences between the different nations, destroying localness in order to create a homogenised green tangle. The contingent aspect of this piece, like Michael’s use of the word ‘I’ in several of the titles of his pieces of work6 is a refutation of Barthes’s contention that the voice has lost its origin.

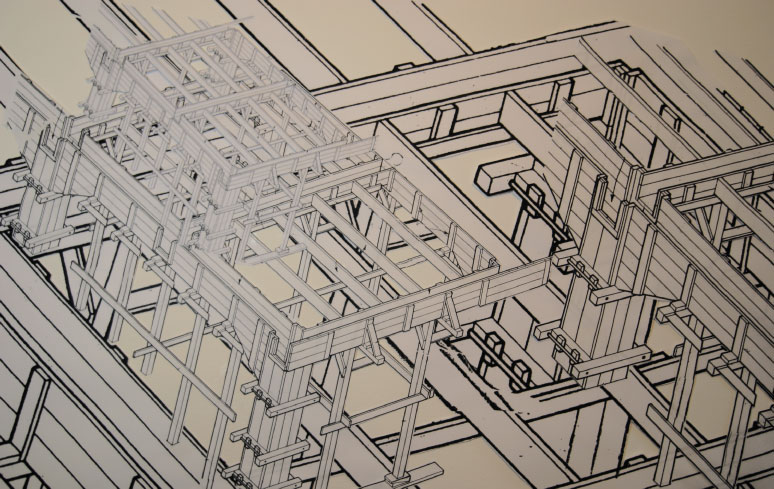

An examination of the drive towards single world civilization, which wears away at the cultural resources of each individual nation, also formed the basis of Paul Ricouer’s book History and Truth. He asked, ‘Whence the paradox: how to become modern and return to sources: how to revive an old, dormant civilization and take part in universal civilization.’7 Some of these tensions can be identified in Michael’s recent collaboration with a group of other Cypriot artists8– which aims ‘to create a social-political manifestation that focuses on the role of the artist as an agent for public awareness who experiments however within a contemporary art context.’ In his attempts to work both within and against the system, Michael’s practice can be meaningfully compared with that of several other artists making work that falls between sculpture, performance and architecture. Michael’s Under Construction (2003) a series of drawings and an installation comprised of planks of wood riveted together into a makeshift environment, could be compared to works by the German artist Manfried Pernice. Pernice’s atelier which formed part of his 2000 exhibition in the Hamburger Bahnhof is a well-known example of his practice of making sculptural pieces which are deliberately left ‘undone’. In Pernice’s walk-in construction Europa (1998-9) faulty architecture is again used as a metaphor for poorly planned and executed systems. Similarly, Panayiotis Michael’s unreliable structure creates a visual analogy of the ongoing ‘Cyprus problem’ and the various plans for its solution that have been presented over the last three decades. The plan-like drawings which accompany the sculptural element are part of his working process of working without the intention of ‘ending or any final result, as a continuation of the ‘under construction’ concept’.9

Panayiotis Michael’s The Dreams I Still Have for Us (2003) is an installation that replicates a border-crossing, composed of layers of wooden fencing, plastic mesh, cordon tape and lengths of rubber hose. These elements are punctuated with greenery, plastic flowers and picture postcards of Cypriot beaches. The inclusion of a small souvenir donkey, a model plane and car self-consciously allude to the rapid transition of the island from a predominantly rural and traditional setting to an affluent, materialistic society, within the last 20 years. Precursors to this piece can be traced in Hélio Oiticica’s 1960s participatory environments and assemblage works by David Hammons like Public Enemy (1991), a barricade made using sandbag and police barricades and armed with prop weapons, festooned with confetti, balloons, leaves and paint. Both Michael’s work and the earlier pieces by Oiticica and Hammons are connected by their attempt to assert the presence of a problematic material world within the abstract realm of the museum. And, as with Oiticica and Hammons, the cultural specificity of Michael’s materials articulates aspects of a contingent and heterogeneous situation.

However, there is an important sense in which the border so often found in Panayiotis Michael’s work is being used to discuss the separation between the self and the romantic Other. Simone de Beauvoir wrote that for the woman in love, ‘the centre of the world is no longer the place where she is, but that occupied by her lover; all roads lead to his home, and from it.’10 This sense of an imagined relationship, constructed through rehearsals of possible conversations and ways of touching, figures in both The Dreams I Still Have For Us and in the four drawings which accompanied Under Construction, entitled To Approach You, Plan - Part 1,2,3 and 4. These drawings are in some way akin to dance lesson diagrams, the numbered footsteps and lines of movement inadequate to convey the real experience of dancing. But there is also a sense of hope contained in plans. Panayiotis Michael says that his drawings function as a way to ‘organise a journey, promising to escape (maybe) from a certain situation and enter a different one’.11

All roads on the endlessly plotted journey of Panayiotis Michael’s recent work lead to his contested homeland, this difficult love. There, his imagined plans could yet translate into specific resolutions. Noam Chomsky wrote recently that it is possible to discern two trajectories in current history: one aiming towards hegemony; the other dedicated to the belief that “another world is possible”.12 It is towards this other world that the practice of Panayiotis Michael turns – there his constructive alternatives of thought and action may in fact be realised.

- Roland Barthes, The Death of the Author, Image Music Text, in English translation, Fontana, London, 1977, p.147.

2. Terry Eagleton, The Illusions of Postmodernism, Blackwell Publishers Ltd., London, 1996, p.131. - Panayiotis Michael, Artist’s Statement, 2003.

4. Christopher Hitchens, Hostage to History, Cyprus From the Ottomans to Kissinger, Verso, London and New York, 1997, this edition 1984, p.160.

5. Thirty years on, in April 2004, the UN Secretary Kofi Annan proposed a new reunification plan which, following twin referenda, failed to be endorsed - certain key terms of the plan were judged to be unacceptable by an overwhelming percent- age of Greek-Cypriot voters. - Look At What I Do for You (2000-1), The Dreams I Still Have for Us (2003), I am Innocent (2003).

7. Paul Ricoeur, Universal Civilization and National Cultures, 1961, History and Truth, trans. Chas A. Kelbley, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, 1965, pp. 276-7, quoted in Ken- neth Frampton, Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance, Postmodern Culture, Hal Fos- ter ed., 1983, this edition, Pluto Press, London and Concord, Mass., 1985, p.16. - The Artrageous group was formed by Klitsa Antoniou, Panayiotis Michael and Melita Couta in March 2004.

- Panayiotis Michael, in response to questions sent by the author, April 2005.

10. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 1949, in English translation 1953, this edition Penguin Books, London, 1974, p663. - Panayiotis Michael, in response to question sent by the author, April 2005.

12. Noam Chomsky, Hegemony or Survival America’s Quest for Global Dominance, 2003, this edition Penguin Books, London, 2004, p.236.

Both texts appear in the official catalogue of the participation of Cyprus in the 2005 Venice Biennale entitled Gravy Planet

Exhibition History

2005 Gravy Planet, (with Constantia Sofocleous), Biennale Di Venezia, Italy, curator Chus Martinez

http://www.cyprusinvenice.org/2005/index.cfm

2006 I promise you will love me forever. Before and After, Rena Bransten gallery, San Francisco, USA. Curator Leigh Markopoulos http://www.renabranstengallery.com/Michael_Tour06.html

2006 I promise, you will love me forever, Before and After, Centre of Contemporary Art Diatopos, Nicosia, Cyprus

http://www.diatopos.com/panayiotis-michael.html

2006 Meghiddo, Notgallery, Naples, Italy, curated by Luca Vona, with: Peter Donaldson, Franklin Evans, Panayiotis Michael, Federico Solmi http://www.nonsolocinema.com/MEGHIDDO.html